Ok Google, whodunnit?

The discovery of former police officer Victor Collins’ battered body floating in a blood-stained hot tub was a grim one. But police who began probing the case in November 2015 probably didn’t realise his murder would trigger a dramatic court battle over an unlikely witness to the slaying – an Amazon Echo.

Collins’ killing at the Arkansas home of his friend James Bates sparked a legal tussle as Benton County prosecutors sought to force the internet giant to disclose recordings that could potentially have nailed the killing to Bates. They said the voice-activated device may have recorded what happened to Collins, or offer significant clues about the run-up to his death.

Bates denied the crime – and in April 2017 volunteered access to the relevant data. He did so before a judge could rule whether or not the Amazon Echo had a First Amendment right to privacy. Later, in December 2017, the murder charges against Bates were dropped but the wrangle had already made headlines across the globe, highlighting how the growing popularity of “always online” Internet of Things devices mean our homes now offer police a wealth of potentially useful data, should we become victims of crime.

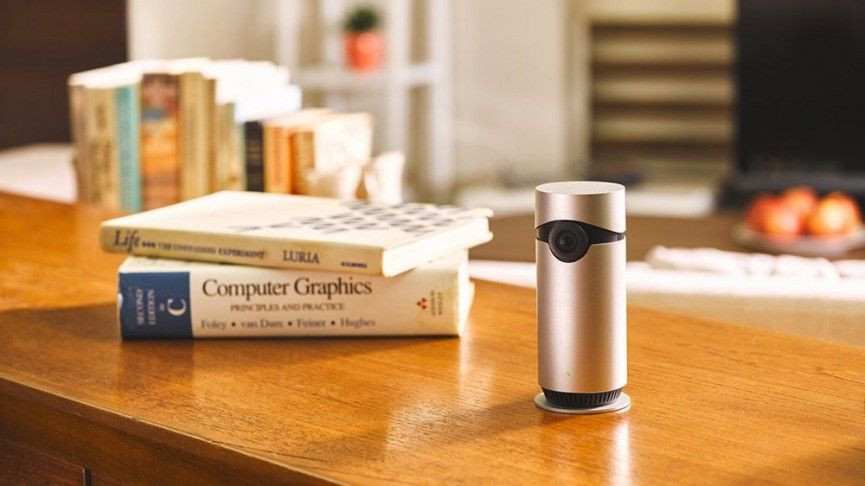

Everything from doorbells that connect directly to smartphone apps – showing who has rung and who hasn’t – fridges with in-built cameras, and even washing machines and smart light bulbs are now potential witnesses.

Law enforcement officials, legal experts, scientists and corporations are already working hard to exploit the growth of IoT devices, while also trying to maximize the chances of accessing any useful data. In the UK, detectives are now being trained to look for connected home devices that could hold clues. Clive Halperin, a London-based lawyer and tech expert is enthusiastic about the prospect of “smart” crime scenes. “I think [IoT devices] will help generate a lot more evidence,” he tells us. “When things are constantly connected to the internet, it’s going to provide a huge amount of data for crime solving. People will be constantly leaving electronic ‘trails’ wherever they go.

When things are constantly connected to the internet, it’s going to provide a huge amount of data for crime solving

“You’ve got the Echo that will know when you’ve been at home, or remote-controlled heating and lighting systems that establish a routine. When you’re out and about, your Fitbit or Apple Watch will keep tabs on you, and provide a constant stream of data on your whereabouts. This data can be looked at individually or collectively, to help potentially establish a person’s whereabouts, or flag up any deviations from a routine.”

It’s something that reared its head in another 2017 case where a man was charged with his wife’s murder after her Fitbit data contradicted his story. Clive insists IoT is a force for good, despite privacy campaigners fears of a nightmarish 1984-style world where every move is monitored by shadowy hidden figures. “There are privacy issues,” he says. “What do these IoT devices actually listen to? Everything that goes on around them or just what happens after hearing their wake-up phrase?

“But I think most people are less bothered about privacy than they once were – most don’t really seem to mind. They share their data, they trust companies like Google, Amazon and Apple. It’s partly because of the convenience and real improvements to quality of life their products have helped bring about. But there’s also that feeling of ‘If you don’t do anything wrong, then what do you have to worry about?'”

Crime-fighting potential

Professor Jeremy Watson, an expert in the IoT based at University College London, is also enthusiastic about its crime-fighting potential. But Watson, who is the director of an IoT research hub in Britain, stressed that standardisation is key in maximizing IoT devices’ usefulness as a crime-solving tool.

“The internet of things could prove extremely useful with crime fighting,” said Watson. “My feeling is that it will become perfectly legitimate for agencies like the FBI or [British] Home Office to have access to this data. It’s something that’s starting to emerge.”

And this is why standardisation is so important. It is what will help generate evidence that can be used in court. “Unless manufacturers, developers and the authorities share some common standards it is going to be hard to establish any sort of coherence with collecting or using data gleaned from IoT devices,” says Watson. “Some kind of standardised symbol of quality – like the EU ‘Kite Mark’ – is a starting point. We are starting to see that with hardware, but we also need to look at the upgrade path of the IoT device.

“These days the hardware may be standardised, but the upgrades and firmware may not know. We are encouraging small to medium-sized companies to start up and do wonderful things. But a lot of these goes bust, so what happens if they’ve got 100,000 devices out in the field, they go bust, there’s no more support for those. People continue to use them, but they’re actually unprotected, so hackers could get in, because there haven’t been any upgrades.”

Professor Watson’s warning also raises the worrying prospect of a two-tier justice system. All the experts we spoke to highlighted how IoT devices could also be used to absolve suspected criminals of any wrongdoing, with their watch or phone providing a cast iron alibi for their whereabouts.

They also highlighted how there is still the potential for their data to be manipulated to set someone else up, however it will be far easier for those with deep pockets to extract data that could clear names when it’s held on the servers of a smaller firm gone bust.

A UK policymaker and IoT expert, who spoke to us on the promise of anonymity, raised concerns over the integrity of these systems: “Although IoT devices are largely secure, there are still ways that they can be manipulated. If a device is registered to you, but not secured by biometric measures, how do we know you were definitely using it at the time of the alleged wrongdoing?

“Obviously, this is the kind of thing any good defence lawyer would flag up during police questioning or during a criminal trial. And although they are rare, miscarriages of justice do happen. Unfortunately, it would be far easier for someone wealthy to hire experts capable of disproving this so-called evidence than someone else of more limited means.”

Our experts also agreed that IoT devices themselves could, in some cases, even encourage crime. They highlighted their potential vulnerabilities to hacking, whereby burglars – or worse – could use data from IoT devices to work out when a victim is or isn’t at home. This digital routine could then be used to plan a crime against them.

Prof. Watson highlighted the importance of “cyber hygiene” – such as ensuring anti-virus software is up to date – to avoid IoT devices falling victim to hackers. “We recognise that it’s a running battle if we’re going to keep attention on the IoT as threats [to its security] emerge as the technology moves on. It is under good scrutiny at the minute, and in general I think it’s going to be a great thing.”

This is just the start, though, and as the smart home becomes more vigilant, more knowing, the greater a force it will be in the fight against – and perhaps sometimes in aid of – crime.