The challenges of creating apps for our voice

For the past 30 or so years, developers have been building applications intended for displays. From computer monitors to touchscreen displays, the way we’ve interacted with our devices has been heavily visual.

In the past couple of years, thanks to the likes of Alexa and Google Assistant, particularly on smart speakers, that paradigm has shifted. We’re not only clicking and dragging, swiping and tapping now, but talking to our devices too.

Read this: The best Amazon Alexa skills for your Echo device

At the forefront of this has been Alexa, as Amazon has managed to enlist an army of developers for its own app store. But this one is all about skills – apps and games that all work around voice. So what is it like being at the forefront of this revolution? We asked the people building it.

The wild west

Palle Sivasankarreddy (who goes by the name Shiva) leads Alexa development at Click & Pledge, a company that helps non-profits build technology to keep track of donations. He tells The Ambient that when the company first started exploring Alexa development two years ago it was hard to know where to start.

“When we started developing on Alexa, at the time there were no great resources to learn about Alexa,” he says. “The basics were covered, and the resources basically explained that ‘if you design the application like this, you get a response like this.'”

However, that wasn’t enough for Click & Pledge’s skill, which was intended to give its clients an easy way to get reports about donations. Click & Pledge wanted to reduce friction, cutting out having to log into a website and app. You would simply ask Alexa and get a response.

Yet Shiva and his team had questions they needed answered. They needed to figure out how to work in authentication, so that clients could easily gain access to their information, and how to plug in the company’s authentication into Amazon Web Services and its various tools. So Shiva and his team started studying, reading whatever documents they could about Alexa and its development process.

Steve Tingiris, founder and managing director of Dabblelab, which helps companies adapt their applications for voice, concurred, saying that Alexa’s development resources and tools have grown increasingly better over the past couple of years. However, now that actually developing skills is much easier, there is a bigger problem.

Building a new century interface

Developers have been building apps with visual design philosophy for decades, and developers have gotten good at understanding that visual experiences are very guided, says Tingiris.

“So if you want a user to do something you can put a big button on the screen that says ‘click here’ and you know that’s the only thing they can do, and you’re pretty sure that’s what they’re going to do.”

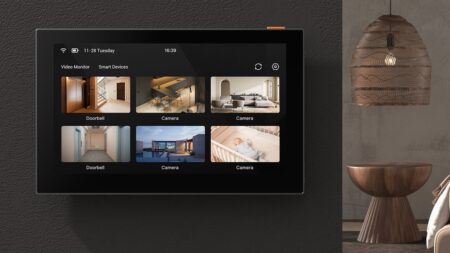

That is turned on its head when it comes to voice. Save for the visual voice devices like Echo Show and Spot, Tingiris says, “in most cases you’ve just got someone who’s just looking at a device and you have no idea what they’re going to say.”

The challenge then becomes how to design for something that’s tough to predict. Kamran Razvan, CEO of Click & Pledge, tells The Ambient its goal has been to try and listen and to understand what possible questions someone might ask as you “can’t ask people to memorise a whole book before they interact with their application.”

The rigidity of voice assistants is one thing all the developers we spoke to expressed some dissatisfaction with. The problem, according to Razvan, is that regular people naturally want to speak to assistants as if they were people. When they end up speaking to something that’s a little more rigid, they get frustrated.

Developers said they have to consider all the potential ways someone could ask its skill for an answer and then program that in. In this way, it can make information reporting with Alexa feel as natural as talking to an actual person. And really, that’s where the bulk of time developing a skill goes to, says Tingiris.

“80% of the effort that goes into building these skills is probably going into testing and refining the user experience, and the things that users can say and how they can say them and the different ways they can say them.”

If you look at the evolution of the desktop and put that parallel to audio, we are at the DOS stage of development

However, there’s debate amongst developers on how far they should go in making Alexa as easy as possible to use. Tingiris says about half the community is looking to build skills that feel and respond as human as possible, while the other half considers voice like any other computer interface, and think that us humans need to better adjust and learn how to properly use them.

In the end, that may end up being a problem that solves itself in time. “If you look at the evolution of the desktop and put that parallel to audio we are at the DOS stage of development,” Razvan says of where voice development is right now.

Tingiris says this doesn’t just include developers figuring out how to get Alexa to feel more natural; it’s about finding ways to make Alexa tell people what it can do without feeling like an automated phone system.

As developers figure out how to better create skills, there’s a generation growing up with voice assistants in their home. There have already been stories of babies saying Alexa as their first word, and our own Paul Lamkin detailed how his two-year-old has learned to command Alexa.

This generation naturally understands how to use Alexa better than we do, and as they grow up and become developers themselves, developers believe that services like Alexa will explode.

The developer wish list

Alright, so developers are plugging away on figuring out how to design all these Alexa skills. But is there anything Amazon can do to make their lives easier? The developers we asked were pretty happy with how quickly Amazon is updating Alexa’s capabilities, and how many resources are now available.

Razvan and Shiva still hope that Alexa could become better at deciphering intent in user interactions, adding to its natural language capabilities. This includes features like follow-up questions, which Shiva says is a big help because developers no longer have to maintain sessions with Alexa, which potentially increases engagement.

In terms of features, Tingiris is hoping that Alexa gains a more advanced version of an ability Siri is about to get in iOS 12. “I’d like to see [voice assistants] evolve to the point where they’re programmable by voice – so a future where users can talk to their assistants to build skills.”

Apple’s Siri Shortcuts allows users to build their own routines that can be prompted with a simple command, but it still needs to be built via an app and a visual interface. Tingiris is hoping that Alexa could one day let users talk to it and build it with less friction.

So you could say something like, “Alexa, if there’s traffic on 101 North, send a text to the people in my meeting telling them I’ll be late” and have all that done for you.

Ironically, Tingiris notes that the future he would like to see for Alexa would actually mean developers wouldn’t have to tune all of these skills for voice. Users, with the help of Alexa, would be able to do it all by themselves.