And sleep enhancing tech is its gateway drug

What smart home gadgets really need is a manual to humans. Because they still don’t know us very well.

Whether it’s one MIT project that measures a person’s gait when walking, and how that related to their overall health, or another MIT project that can locate your body in a room, even through a wall, the research is well and truly underway to start building the wellness smart home.

Sure, it will involve a whole bunch of sensors, and startups are already experimenting with combinations of these and ways to visualise this data and make it useful. And at-home connected health tech monitoring is coming on leaps and bounds, with schemes by the likes of the NHS.

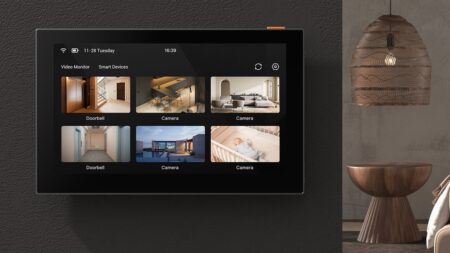

Yet, it’s more than that. Andy Rubin’s new smart home hub, the Essential Home and its Ambient OS, promise to know the layout of our homes and all sorts of information about its occupants, all while this data is processed and stored locally to manage privacy (The importance of this is no coincidence, privacy is crucial to this whole idea).

We thought we might have to wait a while until the concept of the wellness smart home became more pronounced, but we’re already starting to see signs of life in the idea. Here’s what it actually means, and where it could go next.

It starts with sleep

Like most good endeavours, the wellness smart home begins with sleep. This is the first real, tangible benefit that tech companies can attach to these sensors and the data they create. (Smart scales are another interesting bridge to get us to the wellness smart home).

Some devices are able to track an insane amount of data like the effects of ambient noise, light and temperature, UV light, carbon dioxide, barometric pressure, light temperature and volatile organic compounds (whatever they are).

Overkill perhaps, but early adopters will choose a nice, long spec list over a shorter one any day and the more you begin to consider your environment, the more there is to consider. If you really wanted to push this stuff, you could say we’re walking through our homes like zombies who have no clue what is going on around us. Smart home wellness sensors can be the night vision goggles we need to see the true picture.

And you can see the appeal, particularly to families with young kids, say. The quantified self heads home. To stop constant fretting, though, the best systems will ‘just work’, to borrow a phrase. Sure you could show me a percentage and a warning about the air quality, but I would prefer if you did something about it instead.

It’s not just sleep tech startups you’ve never heard of getting in on the act, either. The big names haven’t integrated these sensors yet, but just wait for the next generation of smart home hubs. On the straight smart home side, we already have one of the latest devices from Netatmo, a French company which also sells things like a nifty smart security camera with face recognition. The £89.95 Healthy Home Coach is on the Apple Store, as it’s HomeKit compatible, and is designed for any room of the house not just the bedroom. It uses four sensors to track all sorts of metrics like temperature, air quality, humidity and noise levels in your home.

The idea is that you tap the top – or ask Siri – to get an update on the ‘health’ of the room, as Netatmo calls it, or just set up the Home Coach to alert your phone when you should turn a humidifier on or off, for instance, for asthma or allergy sufferers.

Sleep is mentioned in the sell, specifically with regards to ambient noise, but it’s not the only reason you might be interested, Netatmo cites everyone from studious teens to sweaty toddlers (and their parents) as people who could benefit from tracking and tweaking their home environment more. Expect to see plenty more where this came from.

Connected self + smart home = that’s a bingo

And just think: maybe wearables which purport to measure something tangible in our lifestyle would be much more useful if they were in sync with our homes (and offices etc). So devices like Lys, a clip-on light sensor track how much bright light you get in the morning and how much blue light in the evenings, together with how this could affect your circadian rhythms. In tests, it is being used in tandem with special smart lights – why not hook up existing Philips Hue-style lights to give us what our bodies crave and need?

Stay with me as I get a bit futuristic here, but there are a number of different ways wearables and the smart home could work together in the next five years. For me, personally, I’m using eyedrops at the moment, as my eyes are dry from overwearing my contact lenses. Both my time spent staring at a computer and office air con are no doubt contributing to this – it would be great to have a system at home that monitored both my health, in this case my eyes, (smart contact lenses maybe or smartglasses) as well as the factors around me that are affecting said health.

I already use the software f.lux to warm up the light on my MacBook a few hours before I usually go to sleep but it gets annoying when I decide to watch some Netflix. Why shouldn’t my environment – screen light, temperature, windows, blinds, humidity etc etc – adapt constantly to what I need it to be?

Of course, in the office – and family homes, to an extent – it’s a different picture as there are many bodies and one communal space but perhaps this kind of data could inform office layouts that stop squabbling over room temperatures and noise. Or at least individual’s bedrooms could be a safe haven that’s ‘just right’ for them.

What’s happening with the Amazon Echo family and Google Home, and the rest, is that AI assistants in the home are getting to know our minds, our habits, our queries and our work schedules. But they don’t yet know much about the rest of us. To Alexa, we’re just inanimate, floating voices rather than bodies that breathe and sweat and sneeze. Not for long.

Do you like the idea of a smart home that looks after you in the background? Or does that sound a bit creepy and you’d rather just chat about weather and sports to an AI assistant? Let us know in the comments.