Connected tech is being used by domestic abusers – here's what could be done

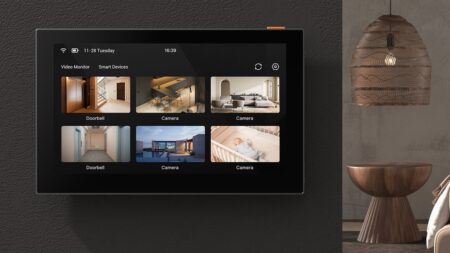

In late June, a disturbing New York Times report detailed how smart home devices – from thermostats to lights to door locks to cameras – were being used by domestic abusers to monitor, confuse and terrorise their victims, often women.

While many of the fears about smart homes are down to external forces, such as governments or other groups, hacking your device and commandeering them for their nefarious purposes, a fear often not considered is what people who are routinely in charge of them could use them for.

Read this: Building a smart home isn’t family friendly enough

Brad Russell, research director for the connected home at Parks Associates, tells The Ambient that once the NYT report came out the company had lots of internal discussions about the impact of this revelation, and how the problem might be solved.

Before you can fix the problem though, you have to identify the weak spots in how we interact with our smart homes. The first one is right up front: it’s the process in which we set up our smart homes in the first place.

The problems

As detailed in the New York Times piece, men are typically the ones who acquire and set up smart home equipment around the home. Thus, they’re the ones who typically go through account creation.

“The way all of these devices and apps associated with them, and accounts, are set up is there’s centralised control by an admin who initiates, downloads the app and syncs the device with the app and has control,” says Russell. “And that’s for a reason, obviously, because there are fundamental data privacy and security issues that are remedied by authorisation of an authorised user that has control.”

There are two immediate problems here, though, says Russell. The first one is that people are different. Not everyone has an interest in learning how to control the fancy new thermostat. Not everyone is gung-ho about installing a new app and creating a new account. People use these apps differently, and they want different things from smart home devices.

Secondly, if there’s an abusive person vying for power, they may not let anyone else have control. This poses a problem, because when they get abusive, there’s no equal way to get rid of them. “If they don’t cede administrative control then you can’t block the admin,” says Russell.

We kind of assume that there may be a technological fix. There might not be. What we’re really dealing with is a human character problem.

And that’s even if your app or service lets you create a shared account. Another huge problem is that some apps and devices don’t even have the option.

These products don’t have family accounts enabled, and everything is done with a singular account. This means that users have to share the same email and password, which means that if someone wants to restrict access they just need to change the password. Because the other users don’t have access to the main account’s email address, they’re locked out.

Another problem is that the person who didn’t set up the account often doesn’t understand who made the smart home products in their home. Sure, people understand that Alexa and Echo are from Amazon, and that Google Assistant is from Google, but there are many companies in the smart home world that aren’t such mainstream brand names.

The somewhat terrifying part, however, is that the issues outlined might not even be the real problem. The real problem might just be us, according to Russell.

“There may or may not be a technological fix,” he says. “We kind of assume that there may be a technological fix. There might not be. What we’re really dealing with is a human character problem.”

The solutions

Do smart home companies have a responsibility to provide some solutions? If you look at it from a functional point of view, smart home manufacturers are giving people the additional power of remote control. In short, with more power comes more responsibility.

“If you’re bringing that into their life and giving them that ability, I think you have some responsibility to consider how it could be used for harm and how you could detect that,” an exec of a smart home company who wants to remain anonymous tells The Ambient.

So what could they do? One solution is to provide more control. Some smart home products, like smart security systems, door locks and thermostats, already offer a number of ways to control them: You can use the app or you can use controls on the device themselves.

“Manual on-board controls of a device are at least a stopgap, so if there’s remote abusive behavior through the app then whoever is in physical proximity of the device could turn it off, or adjust the settings, or somehow respond to mitigate the abuse,” Russell says.

Unfortunately, smart home devices are also pushing more and more smart features to companion apps. And entire categories of smart home products, like cameras and lights, are largely controllable only via apps (however, in Europe there are some smart cameras that come with pull-down shields to cover the lens).

In that case, one way to make smart home products that better protect homes is to, quite simply, make them smarter. It could all start at the setup process itself, with an understanding that not all households are the same. Homes can carry families of all types, from a single person to a married couple to an inter-generational gaggle of people.

This could create a smarter home that uses AI to figure out when it’s being messed with for abuse and shut it down.

One possible solution is to craft product setup in a way that attempts to customise smart home products for people. This could include an app that asks how many people are in a home and what kind of relationship they have to each other and to the home itself.

This could create a smarter home that uses AI to figure out when it’s being messed with for abuse and shut it down. For instance, if someone turns on a light in a room, and then someone remotely tries to turn it off, perhaps the AI system could realise that someone is in the room and that turning the light off is a conflict and not do the action. This of course creates its own set of design and ethical challenges.

Imagine having a UI that doesn’t do what you want it to do. It would be frustrating because it would feel broken, right? The challenge for product designers then becomes designing a product around that feature without making it feel broken for the 99% of cases where remote abuse isn’t happening.

There are a number of potential solutions to that, including cross-checking GPS, Bluetooth and Wi-Fi to make sure someone approved is in the area of the smart home. Of course, that opens a box of new questions: How does that person get approved, and can an admin de-approve them?

The other smart solution is to train smart home products to recognise and report abuse. Smart assistants like Alexa and Google Assistant always have an ear out for their own names, so if they listen out for signs of abuse, or can cross check it with camera footage and weird device patterns (like setting a thermostat to 100 degrees) then maybe it could alert the authorities – or at least ask a user if needs to alert the authorities.

The responsibility

Of course, that also opens up its own problems. There are severe privacy implications, and it risks turning the world’s biggest tech companies into watchdogs trying to solve human character problems. Plus, the technology would have to work with 150% certainty to avoid falsely reporting benign incidents, like a regular quarrel.

In the end, the only solution might just be the simplest: educating people about how their devices work and how they could be used – in good and bad ways.

“A lot of this is educating people,” the exec says. “What are you truly getting here, what is this technology in your home, and why should you care? And yeah, a professional installer could do that, a great in-app setup experience could do that.”

At the very least, smart home companies could create customer service processes that work through domestic abuse. Perhaps it’s as simple as re-enabling or disabling access for out-of-the-ordinary device patterns that are abusive, or even just passing someone along to a domestic abuse hotline.

Like everything else in this tangled web of an issue, that presents its own problem, according to Russell. “It does take [smart home manufacturers] into a completely different place. That’s a social support thing, that’s the role of law enforcement and mental health providers. That’s not the role of a product manufacturer. They don’t have the skill set for it, they don’t have the mechanism for it, and they don’t want the legal liability frankly.”

When asked for comment, August, Amazon and Nest did not respond.

In the end, the only way for us to truly protect the smart home is to build awareness. The more we dive into the potential problems of our more convenient and fancy homes, the more we understand how we can help when things go wrong – or even how we can take steps to protect ourselves.